The finest works of literature can sometimes make for the finest works of cinema, and the list of film adaptations is only growing with time

I believe that each reader creates his own film inside his head, gives faces to the characters, constructs every scene, hears the voices, smells the smells. And that is why, whenever a reader goes to see a film based on a novel that he likes, he leaves feeling disappointed, saying: ‘the book is so much better than the film’.”

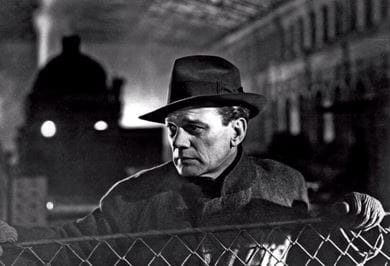

Paulo Coelho, when he says this, echoes an unspoken universal consensus. As far as I’m concerned, a novel differs from its adaptation much as a donkey differs from a carrot. They are two different entities. Of course, there are crossovers, but the most interesting may be the least obvious. I was struck by something John Malkovich said when he wanted to adapt my novel, The Dancer Upstairs. He sought to capture the “sense of loss” that he saw at the heart of the book and which had attracted him to it in the first place. In other words, he was chasing an atmosphere, a feeling, an emotion, a voice. Not enough directors, in my opinion, have this ambition, which is why, for example, so many of Graham Greene’s novels make abysmal films. The atmosphere of Greeneland, a place whose moral temperature would wring sweat out of a refrigerator, is sacrificed or overlooked for the obvious drama, with predictably woeful consequences. Yet when Greene himself was asked to write a screenplay, he understood as could no one else how to peg out Greeneland. The Third Man is for my money one of the best films ever made.

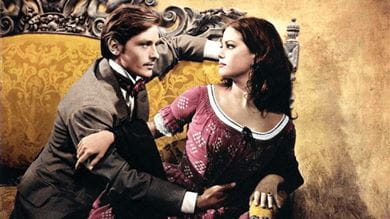

While there have been several attempts across the ages to adapt select literary masterpieces into masterful screenplays, I find that two films by Luchino Visconti – Death in Venice and The Leopard – have come closest to capturing the essence of the texts they are based on. They are faithful to the atmosphere of the original and to the emotion that the reader must have felt when responding to it. The dialogue in the former is minimal – a mere handful of lines. When fidelity to the text is too scrupulous, as, say, in Love in the Time of Cholera, one of my favourite novels by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the result can be more wooden than the fences around Southfork (in Dallas). I also admire the film version of Cormac McCarthy’s novel, The Road. And then there is Apocalypse Now, essentially an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which I thought nearly surpassed the original with its rendition of the narrative. Two more films to do the same have been Dr Zhivago and Jaws.

The screenplay aside, another thing that can make or break a film adaptation of a celebrated novel is the casting. Coelho said it too: every reader tends to attach faces to characters, along with a whole lot else. A more potent problem is likely to arise from the actor’s end, however. “Remember: there are no small parts, only small actors,” said Stanislavski. The problem arises when an actor tries to be bigger than the part. I remember seeing Bruce Chatwin after he came back from West Africa, having watched Werner Herzog, film part of The Viceroy of Ouidah with Klaus Kinski. Chatwin thought the adaptation was going to be one of the greatest films, but this was before the barrage-balloon of egoism, that was Kinski drifted loose from his moorings. In my own admittedly limited experience, actors who tend not to be the brightest balloons anyway, have gained too much power over filmmakers. I was marginally surprised when in The Dancer Upstairs, for which I also wrote the script, the lead actress refused to scream out a line, as indicated, saying that “it would be better whispered”.

Bearing in mind all advantages and potential disasters, however, there is something about film adaptations that lends to them perennial popularity as a genre. This is perhaps why many among them are reincarnated over and over again, each rendition articulating a new ethos and new sensibilities – those of the maker, the writer or simply the age within which it is produced. Take Romeo and Juliet. Shakespeare’s iconic play has been translated into over a dozen movies, some of them direct adaptations of the narrative and others comprising more than a few creative liberties. Macbeth, King Lear, Hamlet, Antigone, Cyrano de Bergerac – all named after characters, I realise – are texts that will always find firm foothold in a cinematic universe. A few other masterpieces – among some of the finest works of literature the world has known – might also make for intriguing cinematic experiences if so translated, such as Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Feast of the Goat and Vasili Grossman’s Life and Fate.

There is, however, no rhyme or reason why a good novel should make a good film. It is a matter of sheer luck. The novelist is compelled to write a novel because it does something that a film can never do, and vice versa. Perhaps in the end, Malkovich is right and for both filmmaker and novelist it is all about a voice. In The Dancer Upstairs, I began with Rejas in the third person. But I couldn’t get into his skull. The tone was flat. His voice eluded me. There are a 100 ways to write a novel, but only one of them is right – and what I was doing was manifestly wrong. I had this wonderful material, but it didn’t begin to fizz until I thought of introducing the Dyer character as a way of teasing out the story. And then, faced by an English journalist much like myself, Rejas immediately began to babble to me in his voice. Talking of the “voice” that you need to find in fiction, I can’t resist quoting Haldor Laxness: “Some voices never manage to break properly. But in all good men there lurks a true note, I won’t say like a mouse in a trap, but rather like a mouse between wall and wainscoting.” That’s what you’ve got to find.

Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre brings to the city a vibrant space for the world of music, dance, ...

I sometimes feel as though the legacy of Lord Kitchener has pursued me all of my life. I studied his ...

In 1992, Prince Charles, the Prince of Wales and heir to the British Throne visited India along with ...

Should one risk a vacation in the middle of pandemic? I thought long and hard about it before decidi ...

The Mona Lisa traces back herself to her artist Leonardo da Vinci’s life at Château du Clos Lucé in ...

The Oberoi Beach Resort, Lombok has undergone rejuvenation and evolved into a destination of unrival ...

A vivid tour through the hottest Bree Street’s central reaches that we call home to the ethical food ...

The Oberoi Beach Resort, Sahl Hasheesh, offers a royal experience amidst the colourful sea life at E ...

Located at the junction of Aravali and Vindhya ranges, Ranthambhore National Park was once a private ...

William Shakespeare lived through one of the most turbulent yet thrilling era’s of English history ...

While central Melbourne has its own allure, the city’s charm lies in its diverse suburbs, each of wh ...

Adrian Rohnfelder, a photographer with a keen interest in volcanoes and adventure, shares his extrao ...

Witness the journey of a wooden instrument that broke all the records to become the backbone of Arab ...

To leap beyond imposed restrictive limits of existence is precisely what Dimpy Menon’s artworks spea ...

More than just a circus, Phare performers use theater, music, dance and modern circus arts to tell u ...

Peru is one of the peak experiences in travel. Nowhere on earth is there such an incredibly wide ran ...

The Oberoi Sukhvilas Spa Resort, New Chandigarh helps you get in touch with yourself so that you liv ...

The establishment of the British Empire greatly influenced the architecture and culture of India an ...

Complete with red sandstone fort, torch lit ramparts and ‘Haveli’ mansions, The Oberoi Rajvilās, Jai ...

Come aboard The Oberoi Zahra, Luxury Nile Cruiser for a delightful mix of luxury and history ...

The incredible Turtle Sanctuary at The Oberoi Beach Resort, Bali, is a must-visit for nature lovers ...

As part of the Beatles, arguably the most iconic rock band of all time, John Lennon and Paul McCartn ...

Oberoi Hotels & Resorts have won the hearts of many with its exquisite charm and glorious stays ...

When I work with a subject, whether it is landscape or nudes, I’m in a relationship with whatever’s ...

Portugal’s capital city of blues from the ubiquitous blue tiling adorning buildings to fado, the sou ...

My conceptual concerts initiate dialogue using various art forms. I wanted to produce works that are ...

From sticky toffee pudding and gastro pubs, to farmers markets, heritage farm meat and stalls housin ...

German art historian Sebastian Schütze, a creative master and precise in technique, captures the hum ...

The Italian art witnessed drastic movements in the period between 1850 to 1950, giving a platform fo ...

All associated with Mughal emperors, maharajas and their courts, the Al Thani Collection is a marvel ...

In the age of art as speculative and subjective, beauty can seem very much beside the point. But sta ...

Complex narratives are the peak of excitement for me. Narratives like double portraits provide stimu ...

At the helm of his eponymous brand, Fendi and Chanel, the late Karl Lagerfeld became as iconic as th ...

Essentially an attempt to replicate a beautiful representation on the canvas, I hope to convey the c ...

The Oberoi, New Delhi’s makeover is an inspiration of the contemporary interpretation of Sir Edward ...

An institution rather than a hotel, the glorious Oberoi Grand, Kolkata is the place tradition calls ...

Ginarte is a journey into beauty, a harmonic synthesis, an expression of strength and delicacy, a hy ...

Oberoi Hotels & Resorts has been ranked the world’s Best Hotel Group at the Telegraph Travel Awards ...

With more than 400 displays, Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, is the ...

Life of the royals in medieval England, especially the queens, was full of intrigue and scandal but ...

The Asian art scene, though young, is booming and art fairs continue to play a significant role in t ...

From ebonised Georgian bracket to 19th-century French brass carriage and the 21st-century Jaeger Le- ...

The East India Company was one of the most powerful commercial endeavours the world has ever seen, d ...

With more than 400 displays, Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980, is the ...

The Oberoi Rajvilas, Jaipur offers an exemplary experience of luxury that transports you to the gold ...

Winner of “Middle East’s Leading Luxury City Hotel” for five consecutive years by the coveted World ...

With elegantly designed villas that offer the best of interiors to its patrons, The Oberoi Beach Res ...

On the north-west coast of Africa lies Casablanca, an ancient exotic land embraced in the sweeping s ...

The new uniforms adorning the staff at The Oberoi, New Delhi are a reflection of The Oberoi Group’s ...

Swan Lake, the iconic ballet composed by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in the late 19th century, continue ...

The Buddha, in his many iterations across South Asia, is most exquisitely represented in gilt-bronze ...

At luxury watch brand Carl F Bucherer, design is about bringing together form and function to create ...

Queen, temptress, politician, murderer: Cleopatra remains an object of fascination for writers, arti ...

Go pedal-to-metal with the best track-ready cars unveiled at the 2018 Geneva Motor Show ...

With an enchanting combination of natural splendour, medieval heritage and modern luxury, The Oberoi ...

The Oberoi Udaivilas, Udaipur, brings together the finest in nature, luxury and impeccable service t ...

The Oberoi Amarvilas, Agra, has been voted the Top India Resort Hotel at the Travel + Leisure, USA W ...

Swiss Photographer Christian Tagliavini captures 15th and 16th-century courtly culture in a series o ...

As innovations in air travel bring the UK and Australia closer, the Kangaroo Route – once stretched ...

The Oberoi, Gurgaon offers a traveller more than just the opulence of a five-star hotel: it is a san ...

In the year 1936, legendary artist Henri Matisse executed with the utmost elegance a charcoal portra ...

The elegant suites at The Oberoi, Mumbai, provide an unrivalled experience of The Oberoi Group’s sig ...

The art collection of David and Peggy Rockefeller has garnered the highest total for any private col ...

The Oberoi Philae, Luxury Nile Cruiser takes you through the highlights of the Egyptian river on a s ...

Complementing its signature old-world charm with the finest of contemporary facilities, this Oberoi ...

Truly great experiences in life, are integral to a design sensibility that seeks to create a visual ...

Modern Indian cuisine is coming into its own, with pioneering Indian chefs like Vineet Bhatia, Gagga ...

Sailing along the River Nile aboard The Oberoi Zahra, Nile Cruiser, explore Egypt’s mystical tombs a ...

Late entertainer David Bowie’s art collection, recently auctioned by Sotheby’s, is an eclectic mix o ...

Majestic lions, magnificent wild elephants and an untouched, untainted landscape weaving together na ...

From Jean Paul Gaultier and Christian Dior to Emilio Pucci and Christian Louboutin, international fa ...

world are among the most highly coveted collectible antiques today ...

Home to the perfect confluence of nature and concrete, Al Zorah gives to luxury travellers the getaw ...

An institution rather than a hotel, the glorious Oberoi Grand, Kolkata is the place tradition calls ...

Combine the exhilaration of a jungle adventure with the relaxation of a luxurious retreat at this sp ...

From exotic varieties to beautiful native species, trees can transform your estate into your own sli ...

The East and the West might speak distinct design languages, but bring them together and a spectacul ...

In the land of the midnight sun, a quintessential family vacation is punctuated by a breathtaking ex ...

The misty Wuyi mountains in Fujian, China are home to Da Hong Pao tea, which can sell for more than ...

Award-winning architect Francis Kéré talks about his design journey and giving back to his homeland ...

In Milan, designer Arthur Arbesser and his associates work and play together, perhaps setting a temp ...

Magnates of the luxury world have been taking charitable steps into the world of European applied ar ...

The culinary offerings at The Oberoi Beach Resort, Al Zorah, reflect its vibe of simple sophisticati ...

The works of 18th-century chaser-gilder Pierre Gouthiere stand testimony to the aesthetic opulence o ...

The inner health of an organisation is as important as the external forces that influence its ascent ...

The artistic traditions of mounted porcelain and enamelling lend a whimsical air to some of the most ...

The iconic Victorian writer and social critic, seen through the eyes of his great-great-great grandd ...

Be a part of the legacy of turtle conservation on the island of Bali at this luxurious beachside hav ...

With impeccable culinary offerings, Mauritian archaeological heritage and the best location on the i ...

As The Oberoi, New Delhi revels in its newly reopened avatar, take a trip down memory lane and follo ...

Passion, craftsmanship and innovation are the defining aspects of Automobili Lamborghini’s design ae ...

As the universe of food undergoes a rapid transformation across the world, The Oberoi, New Delhi’s a ...

Fashion photography is about more than garments and labels - it is about penetrating the physical fo ...

With an artistic masterpiece by Sir Winston Churchill, The Goldfish Pool at Chartwell, recently goin ...

Balancing modernity with its centuries-old heritage, Amsterdam is a study in splendour and historica ...

Dance does not exist in a box and no rules must necessarily govern it. It is a thing of beauty, myst ...

Nestled within an impregnable valley, the “lost city” of Petra is a spectacular expression of cultur ...

Oberoi Hotels & Resorts has been ranked the world’s Best Hotel Group at the Telegraph Travel Awards ...

Ayurveda, natural healing and mindfulness together create a space of rejuvenation like no other at ...

Beginning in the national capital, make your way through these travel hotspots across India that ref ...

Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi claimed a place in auction history recently, setting a new record ...

As the beacon of Western classical music continues to shine bright, a younger generation of musician ...

One fine April morning, 16 actors and technicians set out to take Shakespeare’s Hamlet around the wo ...

From gold snuff boxes inset with diamonds, amethysts and sapphires to ornately enamelled perfume fla ...

The written word, in conjunction with innovations, lies at the very heart of history, shaping cultu ...

August 1947: It had been more than a week since freedom had arrived and the country partitioned. But ...

The Biennale des Antiquaires culminated this year in stunning glory, only to cast its spell afresh n ...

Over the years, I must have observed and recorded the behaviour of at least 125 tigers in Ranthambho ...

The ancient science of Ayurveda tells you how best to enhance your beauty and nourish not only your ...

The gleaming, fluorescent-green topsides of the superyacht Inouï may scream luxury at the Maxi Yacht ...

The world is changing and it is not changing to the benefit of the manufacturers and retailers of so ...

This season, drive in style with these uber-luxurious four-wheeled debutantes ...

The phrase, ‘home is where the heart is’ acquired a new meaning for the children at SOS Children’s V ...

India’s finest private collections of classical Indian art mindfully preserve its creative heritage ...

Make memories last forever by taking your most cherished photographs beyond the frame and photo albu ...

With breathtaking views, luxurious rooms, rejuvenating spa therapies and a state-of-the-art golf cou ...

Seamlessly weaving together traditional elements of Indian architecture, aesthetically landscaped ga ...

Exquisite collectibles going under the hammer are letting connoisseurs acquire a little bit of histo ...

Coming to India in 1865 as the principal of an art school, John Lockwood Kipling made an invaluable ...

When travelling along the path of kings and queens, The Oberoi Hotels & Resorts offer a palatial pla ...

For luxury travellers, the sky is the limit, quite literally, as a gourmet open-air meal at the base ...

From 18th-century ormolu clocks framed by candelabra to enamelled 19th-century timepieces, mantel cl ...

The Emirate of Ajman is home to The Oberoi Beach Resort, Al Zorah, a modern architectural masterpiec ...

The last queen of France was a great commissioner of beautiful things, and several of the shops she ...

From exclusive garments manufactured in Italy to style inspirations drawn from art, this is what the ...

A new facet of Pablo Picasso’s artistic repertoire is taking over the international art market his c ...

Every bottle of vintage wine has a story to tell. We give you the narratives behind five of the fine ...

In the universe of Modern art, rivalry is a complex dynamic that enables one artist to be influenced ...

A story is conditional – it is a matter of perception and might not always be, subliminally or even ...

From unique water and land activities to certified diving courses, desert tours and more, this all-s ...

Enrich your stay in Ranthambhore at this opulent jungle resort, in close proximity to nature, yet ne ...

With performative nuances and provocative appeal, Western classical music has evolved into a complex ...

Second child until maximum age of 12 years will be accommodated in the same room at additional supplement. The additional amount is not included in the room price mentioned and shall be payable at the hotel during check-out.

400 AED (including tax)

250 AED (including tax)